By Cara Eisenpress

Though President Obama’s recent call to invest in the manufacturing sector coincided with reports of growth from American manufacturers, a plan for an ambitious industrial recovery does not apply to New York City.

Here, expensive real estate intensifies the nationwide pressure on manufacturing operations and has squeezed the sector during more than 50 years of shrinkage. That means a manufacturing resurgence of the caliber President Obama spoke about in January’s State of the Union address is a far-fetched outcome.

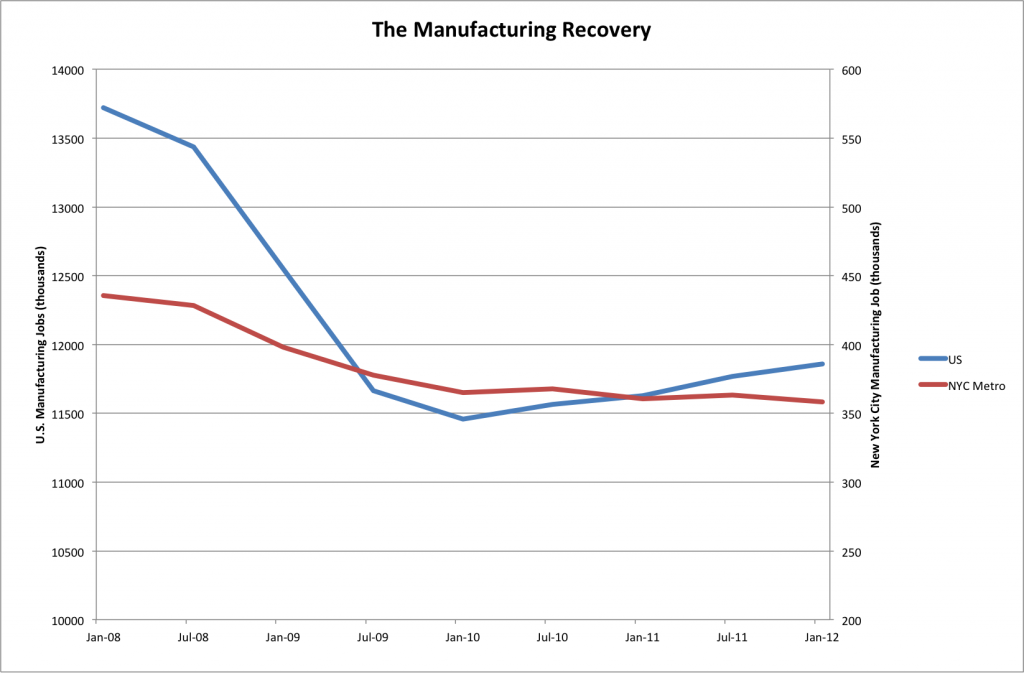

data from U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics

Instead, contemporary New York City industry operates out of smaller spaces, employs a contracted workforce and gets creative with its business models.

The pressure starts with high rental prices. Gentrification pushes residences and retail into historically industrial neighborhoods like Williamsburg, and prices per square foot shoot up. Real estate speculation by developers means any neighborhood’s prices can sprint upwards if it threatens to become hip. A factory that owns its building can succumb to the pressure, too, if it discovers its space is worth more than the business.

“We were about to sign a lease in Brooklyn that would have cost about $150,000 a month just to operate the facility,” said Bob McClure, co-founder of McClure’s pickles, which moved most of its production out of the city in 2011.

He said New York’s costs impeded the firm’s ability to grow from small to midsize.

“If we’re investing so much, we better do it in a place that isn’t going to bankrupt us,” he said.

Instead of paying $11 per square foot on a 4,000-square-foot space here, the company hauled production to Michigan, the founders’ home state, where McClure said its 25,000-square-foot factory costs 22 cents per square foot. The company keeps an office for development and marketing in Brooklyn.

Smaller businesses that aim to stay small can find homes in subdivided former factory spaces and at new government-funded developments like the Brooklyn Navy Yard, which has more than a million square feet of industrial space and a long waitlist. At the Navy Yard, government subsidies guarantee prices for the long term, which prevents developers from speculating. That makes start-up industrial businesses sustainable, said Andrew Friedman, director at the Pratt Center for Community Development.

It does not mean that the new companies can attain the scale of the factories New York City has lost in recent decades, especially outside the borders of the Brooklyn Navy Yard.

“We’re not generating as much new business as the old businesses we’re losing,” admitted Friedman.

Though new models for industry in New York City might insulate against speculation, they cannot rebuild the manufacturing sector that existed here in the past. The companies that remain have to be lean, space-efficient, and simply smaller than the manufacturers of yore, as McClure’s Pickles discovered.

The new industrial companies market innovative products, but they tend to employ five, 10, 20 employees—not hundreds.

While a start-up company may get a break on the price of space, the isolated islands of affordability do not constrain the overall rise in industrial real estate prices. If neither the Brooklyn Navy Yard nor another development, the Greenpoint Manufacturing and Design Center, is a good fit, options are few.

Larger players that stay here, like Brooklyn Brewery, rely on unusual tactics to remain profitable. The brewery occupies a space in Williamsburg where it makes beer—and shows visitors around. Steve Hindy, a co-founder, said that public tours of the facility provide income that’s essential to paying rent.

“I’m not sure that a straight manufacturing operation would be able to do business here,” he said.

Following the recession, the city’s craving for craft beer grew while its desire for real estate limped along, and Hindy took advantage of the cheaper market to expand into a space that cost about $10 per square foot. (He said when he first looked, in 2005, Williamsburg industrial space was running $15 to $20 per square foot.) New Yorkers drink 45 percent of the company’s $40 million in beer sales, and so Hindy prioritizes proximity over saving on square footage. He brews lower-margin beers in a space upstate.

Hindy, Friedman, and others who hope that manufacturing businesses don’t have to leave New York City for good, tend to emphasize how important their sector is to maintaining the city’s diversity, employment, and spirit. That’s why they say government-funded zones like the Brooklyn Navy Yard are essential.

They forget that the market can work for them, too, if they adapt to its realities. Hindy’s landlord is himself a factory owner, who bought the brewery’s space in the 1980s for a plastic bag business he now operates out in Bushwick. And does he rent to Brooklyn Brewery because he is worried about industrial retention?

“He’s a landlord,” said Hindy. “He knows a good tenant when he sees one, and he likes the steady income.”